Du kan lese den norske versjonen av intervjuet er her.

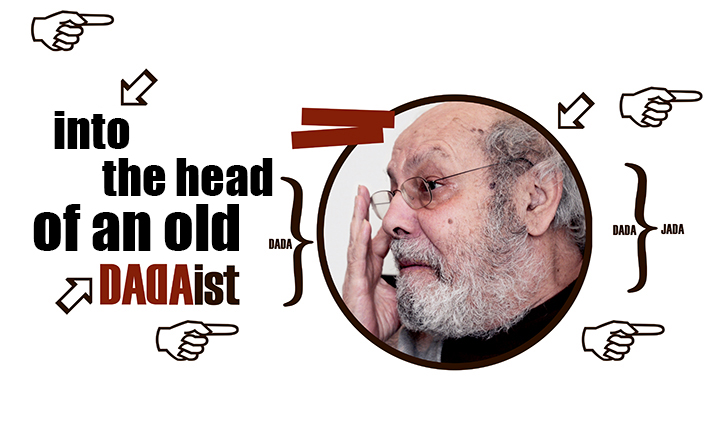

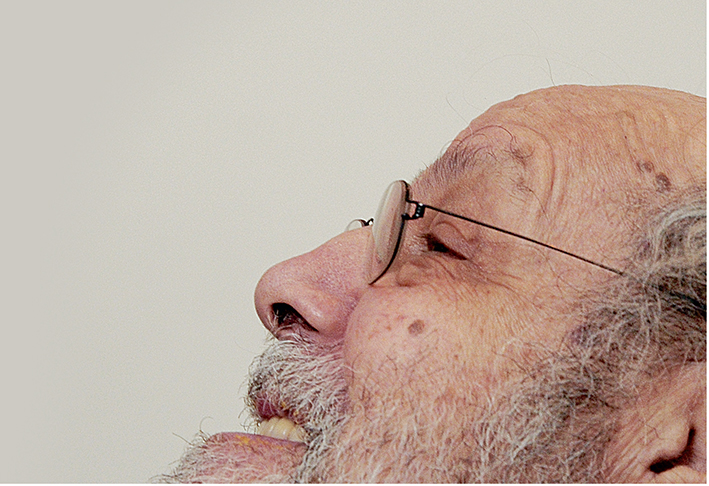

The Dutch pianist, orchestra leader, Dadaist – and all the rest – MISHA MENGELBERG, left our time on March 3, 2017. To commemorate Mengelberg and his lifelong work, we republish the interview our writer, JOHAN HAUKNES, did with our hero at Moldejazz 2011.

R.I.P. Misha Mengelberg,

The article is translated and edited from the original, published interview in Jazznytt. Some editorial changes has been made to adjust it to web publishing. We have tried to keep the tone and time of the original article unaltered. Some changes have nevertheless been made to make the content clearer.

Translation and editing by Johan Hauknes.

Old, but eternally young Misha Mengelberg is in Molde, at the 2011 festival! When the programme of [the 2011] Molde Jazz Festival was published, some of us were quick to mark the concert by Misha Mengelberg in the Molde Forum as an absolute «must» to attend. Mengelberg, our old hero. He was scheduled to play with the young drummer Tyshawn Sorey – a drummer we never had seen live, but had heard lots of praise for.

Of course we were sceptical. It is impossible to see Misha in a duo with a drummer without comparing it to his many duo concerts with his brother-in-arms Han Bennink. Could this young upstart from New York fill the shoes of Han?

However, Sorey did not disappoint us. The concert became a surrealistic experience where the two musicians took it to a very different place than where the duo of Han and Misha had ever been. More about this later.

In the morning before the concert we got the chance of a rare, beautiful hour and more with this Fluxus veteran from the Netherlands – a musician that together with Bennink and the late Willem Breuker created an ironic form of music that fits no – and all – style based classifications of improvised music. A form of music that we today see as a natural and central tradition in Dutch jazz and experimental music. A music that once was very revolutionary.

«Hello, you know I am Dada?»

This is how Misha Mengelberg greets and welcomes me into the sofa where we have agreed to meet. From this, it goes only one way – upwards. Whoever believes that being a Dadaist is about looking squint-eyed and ironic at reality without any seriousness and reflection, need to rethink the issue.

Life is too important, not to laugh about it. Life is important – and meaningless. The meaning we can find in life is the meaning we choose to give it. So simple – and yet so complicated.

Zing zang zaterdag

To write his life, his biography, is almost a royal insult – a lèse-majesté. A biographical description of Mengelberg’s life is in total opposition to the surrealistic philosophy that Misha Mengelberg breathes, is an integrated part of, a philosophy he embodies. Yeah, more than this, the philosophy he is. It is meaningless to depict his life as a meaningful life cycle, as a one-dimensional line that teleologially explains where he is today. With this:

Is it possible to describe a life such as Mengelsberg’s? Definitely not. This musician is stylistically and aesthetically everywhere and nowhere. Impossible to classify, just as much at home in a New Yorkian context with Dave Douglas and Joey Baron, as in a European contemporary music framework. Just as much in John Zorn’s eclectic world, as in his own – a «tongue-in-cheek» ironic world. A world where you never feel quite sure whether he is serious or is making fun of you. Nevertheless …

Mengelberg grew up as a son of the Dutch composer, conductor and pianist Karel Mengelberg and his wife, the German harpist Rahel Draber. Because of his father’s work in Ukraine, he was born in Kiev in 1935, before the young family returned to Amsterdam in 1938. We are told he wrote his first composition for piano as a four year old, a few years before Han Bennink did his first percussion exercises on a kitchen stool in nearby Zaandam.

Both Misha’s father and his grand uncle Willem Mengelberg were working as conductors of the Concertgebouw Orchestra. With a performing musician as mother on top of this, it would seem obvious which way Misha’s life was heading.

But, no! The young Misha wanted to be an architect! He entered architectural studies – at first. However, the music caught up with him. Suddenly he caught the virus, he says, and quickly left physical architecture to devote his life to musical architecture.

As with most of his generation Charlie Parker was an early influence, together with pianists Thelonious Monk and Herbie Nichols. Duke Ellington had a strong impact on him, particularly on the relation between individual voices and orchestral sound. The latter three are also composers that Mengelberg returns to again and again in his performative work.

However, when he started at the Conservatory in The Hague in 1958, he became interested in modern composition and contemporary music. When he attended a lecture series by John Cage in Darmstadt the same year, this was a determining factor for a change in his conception of music.

Cage gave his lecture series, called «Composition as Process», in three parts over four days, September 6, 8 and 9, 1958. His series was given on the invitation of Karlheinz Stockhausen to the «Internationale Ferienkurse für Neue Musik». Today this lecture series has an almost mythical status in the history of contemporary music.

In the years after this, the Cage lecture series has been regarded as a turning point in the history of European contemporary music. In the three lectures, «Changes», «Indeterminacy» and «Communication», John Cage introduced his radical ideas of indeterminacy and the principles for an egalitarian approach to all sounds, including noise and silence, in music. The lectures also implied his break with serial music and European contemporary music.

Hypochristmutreefuzz

When the young Misha Mengelberg returned to The Hague to complete his studies at the Conservatory these new perspectives had definitely influenced him.

Moreover, during his examination period in 1964 he got an invitation to participate in something that lead to the first recording of his piano playing – a recording that for all time will have a very special place in the history of jazz.

When Eric Dolphy finished the European tour with Charles Mingus at the end of April in 1964, he chose to stay behind in Europe. He had planned a longer stay in Europe, well in advance of this tour, as witnessed by the tune Mingus wrote for the 1964 tour of the Mingus Jazz Workshop, «So Long, Eric (Don’t stay over there too long)».

With the Dutch booking agent Paul Karting, Dolphy made a contract for a five days tour of the Netherlands with a rhythm section of local musicians. Misha Mengelberg on piano, Han Bennink on drums and Jacques Schols on bass.

The last concert of the contract was a recording made for the national broadcaster VARA in Hilversum – made for a radio transmission, with an audience present in the studio. This recording quickly gaines a very special status, when Eric Dolphy died in Berlin just four weeks later, 36 years old. It seems his death was caused by maltreatment by the hospital, when he fell into coma from his diabetes.

The VARA recording made June 2 this year has since then, been issued on record several times with the somewhat misleading title «Last Date». Even if it was the last studio recording of Dolphy, it was far from the last time Dolphy played. He was very active during the next weeks, both in Paris and in Berlin – up to June 28, when he collapsed on the stage in Berlin.

Both Bennink and Mengelberg has later said that they really struggled to find the key to Dolphy’s music and his playing. Mengelberg later said that he was sure that Dolphy thought him lazy and uninterested in the music. The recording shows nothing of this, and photos from the tour indicates a relaxed and warm atmosphere.

Furthermore, just a week before he died, Dolphy wrote to Karting, «Thanks for a very sucessful trip in Holland. … Give my best to … Jack and Misja, and … let me know … how I can get in touch with [Han Bennink]». So there is nothing that suggest that Dolphy was dissatisfied with the band and his stay in Holland.

This was the very first recording of Mengelberg’s compositions. The recorded tune was «Hypochristmutreefuzz», Misha says it refers to the chaos of Christmas gifts, cords and gift-wrapping under the Christmas tree. Maybe a paraphrase on Parker’s sound mimicking «Klactoveeredstene»? The tune is a fabulous mix of inspiration from Thelonious Monk, with a solid dash Cecil Taylor thrown in.

He has returned to the tune several times since then. Over the years, increasingly its performance fragmented with an elastic use of time in the performance – listen to the version on the record «Four in One» with Dave Douglas, Brad Jones and (of course) Han Bennink from September 2000.

«Gare Guillemins», the tribute to the railroad station in Liège in Belgian Wallonia, and «Hypochristmutreefuzz» are probably the two most known, and beloved, of Mengelberg’s compositions.

Christmas trees and railroads – what do they have in common?

Met wel beleefde groete van de kamel

When asked how music was in the Netherlands around 1960, Misha Mengelberg a few years ago answered, «terribly dull. [Heinrich] Heine’s statement still applied», referring to Heinrich Heine’s assessment that the Netherlands would be the best place to be on Judgment Day – as «everything happens thirty years later» there. The next years would turn this upside down.

In 1967 Mengelberg, Bennink and Willem Breuker formed the innovative and totally balmy project Instant Composers Pool. Soon the ICP Orchestra was the performative expression of the project. Together with the later Willem Breuker Kollektief, this would be the most important expression for what Kevin Whitehead used as the title of his book on Dutch improvised music after 1960, «[the] New Dutch Swing».

In his book on European free jazz from the mid-1960s and onwards, Mike Heffley describes the free scenes in Great Britain and Germany as follows. British musicians are «sound researchers», characterized by introvert collectivism with an aesthetic of quiet anarchism; static and non-hierarchical in Gestalt and sound.

While the German ones are «energy players», picking up on the most intense, improvisational [and associative] screaming aspects of American free jazz, including their strong emotional expression [both politically and spiritually].

The Dutch scene Heffley describes as the «louder anarchists», the humourists and ironists, the rugged individualists and musical tricksters who created a grass-root, populistic alternative to commercial «pop-schlock» and [pompous] classical Kultur.

Or as expressed by Kevin Whitehead; Dutch improvised music has some special characteristics, such as

« … an impulse towards theater, role play, humor and ironic distance from one’s own creations; killer chops that make all the horsing possible, the virtuosity that assures any fuck-up is deliberate; [and] a certain clunkiness [the Dutch composer] Louis Andriessen calls ‘lousy Dutch wooden-shoe timing’.»

Perhaps it is this clunky wooden shoe timing that explains why Thelonious Monk is so central to what happened later in modern jazz in the Netherlands? Beneath these characteristics, there is an evident surrealistic and Dadaistic approach, both to the creation of music, and to how to talk about it.

In the case of Misha Mengelberg and Han Bennink, we may trace this back to their involvement in the Fluxus movement during the early 1960s.

While the camel, after greeting us, said – exactly nothing.

Where is the police?

Fluxus – from the Latin verb (to) flow – started in 1960 as a radical art journal in New York under the leadership of the Lithuanian-American artist George Maciunas. According to one version of its history, Maciunas took the name from the medical vocabulary, where fluxus denotes a ‘liquid bowel discharge’, otherwise known as diarrhea!

The name does not just point to the ephemerality of art – and thus the need of constantly being in motion, but also at the importance of art being a part of all aspects of life. Moreover, as the medical source may suggest, the need for cleansing. To purge the world of bourgeois sickness, for «intellectual», professional and commercialized culture. To purge the world of dead art, imitation, artificial art, abstract art, illusionistic art and mathematical art. To purge the world for «Europeism»! This was the purpose and manifesto of the Fluxus movement.

Quickly the Fluxus movement became a global and many-facetted network of writers, artists, composers, participants from media, and musicians. Cage’s principles for the relation of music to society were the seeds of many ideas, but the movement also incorporated ideas from composers such as John Cale and the minimalists Terry Riley and La Monte Young. One of the earliest participants was Yoko Ono, an artist Mengelberg and Bennink performed with in London during the mid-1960s.

Today we may describe the Fluxus movement’s purpose as the establishment of an action art – an art form that transcends and dissolves the modernistic division of art and life. Art and living life is an integrated whole. «Das Leben ist ein Kunstwerk, und das Kunstwerk ist Leben» – «Life is a work of art, and the work of art is life» – as Emmett Williams said it.

The participants united, not just in a struggle against an elitist, high culture art, but also in the idea of a total integration of all forms of art. Fluxus on the poster for any performance or happening would immediately mean an integration of video, images, smell, noise, light, movement, actions and the use of any accessible artefacts.

In this perspective, it gives perfect sense when Han Bennink in a duo with Misha Mengelberg is playing on a pizza cardboard box. And as this shows, in the words of Astrid Schmidt-Burkhardt in her essay «Fluxus im Fluss der Zeit» – «Fluxus in the flow of time ») from 2005, Fluxus «develops further … vaudeville, comedy, Dada and Japanese Haikus», in contrast to other radical views of art at the time, that «goes back to the Baroque ballet of the court at Versailles».

The main concern of the Fluxus movement was the question of where the division between art and non-art is – and when the question had been posed; suggesting that the question itself is meaningless. The Fluxus movement’s radical manifesto points directly to performance and action theatre later in the 1960s and into the 1970s, also here in Norway.

Hence, there is a direct line from Fluxus to the total-art concerts of the Svein Finnerud Trio at the Henie-Onstad Art Centre at Høvikodden and at schools and other communal buildings during the years 1968-73, to what happened at Club 7 in Oslo, to the establishment of Hålogaland Theatre [in Northern Norway], and to the stunt poets. It was not just «Art to the people!» and «Art for the people!», but even more: (create) «Art with the people!».

Fluxus was a radical movement, and this radical approach still characterizes Misha Mengelberg in 2011. The goal is not to give a general answer – true in all senses, true for all. The goal is to ask questions. Any question is answered with a new question, and this is what generates progress. There are no final answers – only more questions – to all the existentialist question of what the purpose of art is.

What is the role of the musician? The answer to that question lies in how you, not as a listener, but as an actor, as participant, give meaning to the perception and experience of art. Art is not something that exists alone, isolated and objectively. The work of art is created in the interaction between the performer and the viewer or listener.

The work of art does not exist in itself, but exists only in the interaction between two egalitarian participants – the artist as performer and the receiver as interpreter. Thus, this implies the obvious conclusion that it is meaningless to encourage the artist to describe the objective meaning of the work of art. As there aren’t any.

And equally, the receiver cannot describe the meaning of the work of art «an sich». The only thing she can do is saying something about meaning of the work of art «für mich»! To paraphrase Kant’s fundamental distinction between our perception of the world around us – and this world in itself.

The police had returned home and gone to bed.

I forgot rhythm

During the 1960s, Mengelberg was very active in organisational and political development. He was one of the founders of BIM (Beroepsvereniging van Improviserende Musici) as an organization for improvisational musicians. For ten years, he was BIM’s chair, and led the work of establishing the musicians’ own venue, the Bimhuis in Amsterdam, a venue that quickly established itself as one of the main stages for improvised music in Europe. In 1968 he participated in the creation of STEIM (Studio voor Electro Instrumentale Muziek), and was for many years the artistic director of STEIM.

And he was an active promoter to establish public support schemes for Dutch improvisational musicians. The establishment of ICP reflected this and the view underlying it. Improvisation was «instant composing» and thus compositional music.

ICP was from the start a political organization to counter the dominance of the archaic position that art music was classically composed music. That the only form of music deserving public support – where the state took the rôle as a patron – was only this kind of precomposed art music.

This was a political programme straight out of the Fluxus movement’s manifesto. In Mengelberg’s own words, «we wanted government subsidies … if they can subsidize the Concertgebouw Orchestra, and the opera, and the ballet, they can also subsidize some improvised music. So we went to The Hague to make demands there, and nobody listened.

«But when you go on like that for six or seven years, there comes a moment when they might listen. They don’t want to see you anymore. They’re fed up of seeing you». If you have enough stamina, they eventually fold and give up, not because they accept your views, but simply because they are fed up with you. «So we started ICP.»

And support schemes were established, whether it was for this or other reasons. But these are schemes that still, several decades later, are threatened and has to be defended. As the decision of the Dutch government to end the funding of Muziek Centrum Nederland from 2013, shows.

A decision that was not made because jazz and improvised music is not ‘arty’ enough. Rather the decision came, paradoxically, with the argument that jazz is too elitistic – and thus not popular enough. In the present populistic world it is too artistic, too elitistic, that is why it is not worthy of support from the community. It is too artificial, too much art!

So who’s got rhythm now?

Einepartietischtennis

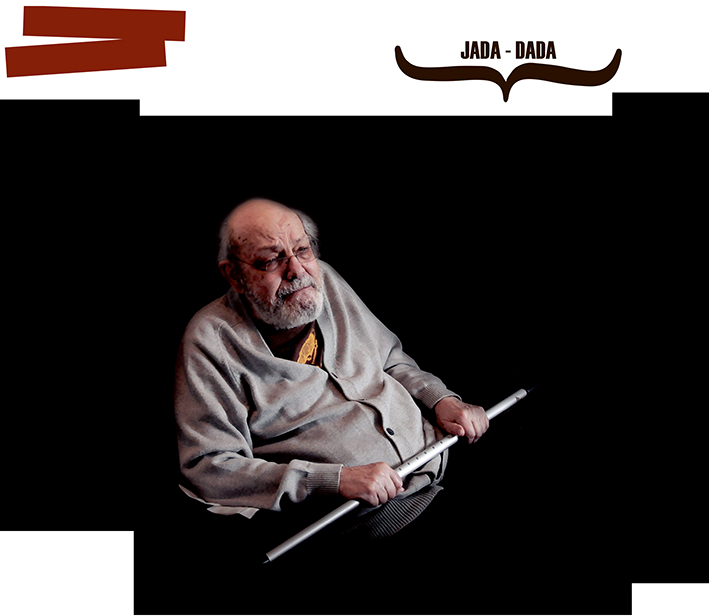

Mengelberg may appear to be frail – and yes, physically he is. It is evident that he needs some time to express his ideas and thoughts in our common language of communication, international broken English. Both physically and because he needs time to find the English words and expressions for his ideas.

In addition his mind jumps around over the landscapes we cover, like the calf of a moose with spring fever. So it is no surprise that it is challenge for the interviewer to follow along his intellectual trails.

Hence, this becomes a conversation in slow time. A conversation where there is absolutely nothing frail about his mental creativity and generation of ideas. But where it takes time to express all these ideas and check that the simple jazz journalist has got the message.

It becomes an educational session, with an artist who is directing both the environment and the individuals around him. When conversing with Misha Mengelberg, laughter is never far away.

In the beginning you are not certain whether he answers your questions or if he is poking fun of you. But the more you listen, the more you understand that there is a deep reflection and seriousness behind the surface, a serious attitude where the jests play a key role.

– This is not the first time you are in Molde?

– No, I was here almost twenty years ago, with ICP. But at that time I didn’t have the pleasure of being interviewed.

– I would like to talk to you about your approach to performing music, your approach to music in any way. Among other things, you have expressed strong views about the relation of notated and improvised music.

– There is a lot to be said about this. I am a Dada-man, I have always been focussed on a «nonsense» approach to whatever happens. The composed music is no longer there when I play. It is ten years since I wrote music for the last time.

– But ICP is still active? With more or less the same participants?

– I don’t think I have changed the composition over these ten years – still it is Wolter Wierbos, Thomas Heberer, Tobias Delius, Michael Moore, Ab Baars, Ernst Glerum, Tristan Honsiger and Mary Oliver.

– Besides you and Han Bennink as the only remaining ones from the beginning. Back in 1967 it started more as a political initiative than a musical one?

– Yes, that was from the beginning – and even before that. There were political issues, but we were always ready to laugh. As I see it, laughing is much more interesting than concentrating on the political issues. Humour and to play is more important than almost anything else.

– Back to your meeting with Dolphy. What did you think about his music?

– He was an OK fellow. I liked his music, but he was not excited about mine. But that is all right, neither do I like my own music. Sometimes I hate my music. Hatred is a stronger phenomenon than other feelings, that is why I like it. Not like being satisfied. I do not like being satisfied.

– You played with him for about a week, wasn’t it?

– Yes. It may be that he didn’t like my music, but I was interested in his. But this was not a topic when we played together. I was interested in his music because it had in it moments of ugliness.

– Dolphy was not a beautiful composer or performer. During the 1960s when I knew him, his own approach carried within it the wish to make everyone happy with his music. This was something that was in him from birth.

– But then he died shortly after. This was an interesting surprise, I have totally forgotten the time when it was sad and sorry. I hope he didn’t die because of my music (laughter).

– The studio recording from VARA, later issued on record in many formats, was originally made for a radio broadcast?

– Yes it was. The recording from Hilversum had this ugliness we were looking for. But some of the people who made the record afterwards, forgot this – the record became too beautiful. The ugliness was something we were part of, something Dolphy got into as well. He could play very ugly. The bass clarinet was especially important for this.

– Bæ-ba-la-du-aladu-chra-chra… That was the way he played. That was his kind of music. Ugly. He was an OK musician, I think.

– At the time this kind of music was completely new, and far out. It was difficult for the audience to relate to. Even though today it is almost perceived as mainstream music.

– Yes, exactly. Noone had heard this kind of music before.

– When we started, nothing were happening in the Netherlands. We started making music that maybe was ugly, then things started to happen. As when Dolphy came to Amsterdam. He unpacked his bass clarinet and started playing his own material and our music. He was a funny guy. He had a great sense of humour. This was very important at the time.

– If I understand you correctly, this was in many ways the start of what we may call the surrealism in Dutch improvised music, with ICP, Breuker Kollektief and all of the things that came later?

– Yes, it was. Breuker left ICP shortly after the start. He said to me he wanted to play the old, bad music. That was what he tried, the things he did with his own orchestra, that he got started right after this. Very intuitive and subtle. I liked much of his music during the early phases, when he played this rotten music.

– Then he went into his beautiful music, and he lost me. That was the really rotten music. He took it too lightly, the question of what was beautiful, and what was not.

– So what you did in this period was developing a new aesthetics, wasn’t it?

– Exactly, that was just what we did. This is quite correct. There was this trumpet player … Breuker liked his music. But he liked better to play his own music. That was all right for a while, but not in the long run. His music didn’t have the same strength as Dolphy’s music.

– When things are good, or nicely done – I don’t like that. Everything else has to do with this. I like the things that are done ugly, not what is done nicely and beautifully.

– Why this approach? Why do you prefer this to the drive to be satisfied with what you do?

– Because the feeling and the music become stronger. Stronger than «beautiful music».

– So it is the strength of the feeling, more than the experience, that there is more to be done, more to strive for?

– Yes, maybe. We are lazy people. Those of us who are still doing this, we prefer to let the music speak for itself. I think I always have felt it like this. That it is the ugliness in the music that is attractive. Ugliness has in it the promise of more ugliness.

– What was it that happened in the Netherlands during the 1960s? Seen from the outside, this was a decade where the Netherlands went from being strict, serious, well-organized – and then, an ferocious flowering of surrealistic and ironic approaches to life in general …

– Yes! And if you had been there at the time, you would have been part of it.

– and a blistering creativity in cultural activity more specifically.

– This applied more Willem Breuker than it applied to us at the time. For me, the necessity to play ugly was still there. I befriended some American people that had some of the same ideas and musical views as me.

21-11, and the Netherlands wins over Norway.

No Idea

– Humour and ugliness played, and still play, a great and important rôle in the music. During the concert later today with this very talented drummer Tyshawn Sorey, [the concert is «reviewed» below], you will hear things that are totally different from what we did twenty years ago. But some elements are still there. It could have continued in some beautiful direction, such as this: mm-mmm-mm (humming).

– Some of us prefers this ugliness in music, that this ugliness is the beauty of it.

– The ugliness does not exist for me. The so-called ugly are things where afterwards you say that this could not have been played in any other way. This is what it all is about.

– The cooperation between you and Tyshawn Sorey, how did it start?

– I was asked by John Zorn to come to New York and play on some event. There are some, like John Zorn, that have a positive attitude to my ugly music. Through him I met Tyshawn. We gave him twenty minutes to demonstrate his music. And immediately I got interested in his approach to playing [and not playing], to creating life in the drums.

– It is difficult to go to this concert without being reminded of your long duo collaboration with Han Bennink!

– [Bennink] is still a very necessary part of ICP. He plays, and some times he likes to play a little too loud (laughter). He has a strong presence.

– How would you compare these two duos?

– For me it was time to enter those things that are not necessarily beautiful – in the opposite sense. This side is a completely natural part of Tyshawn, it is sitting deep in his bones. Thus, we have no disagreement about what we are looking for. He can play very quiet as well! But with a strong presence. This is what is important to me now.

– The most well-known tune you have written, is «Gare Guillemins», I think. Why this tribute ot the railroad station in Liège, Belgium?

‑ A very friendly little tune. Everybody likes it. No, I didn’t write it! I have never written it down! I only play it. Everyone that wishes to play it, must discover its antics by themselves. I do not share any scores or any other material on it. Still I am not doing it!

The railroad station Guillemins in Liège is today a spectacular building, put up in the decade after the turn of the Millenium. The present station was designed by the Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava – an architect that also designed the James Joyce- and Samuel Beckett bridges over river Liffey in Dublin. Thus, also with the architect Calatrava there is a surrealistic thread.

But Mengelberg’s tune was composed at the time the old functionalistic station building from 1958 still was in place.

– But why the railroad station? What is your relation to the railroad station in Liège?

– It was full of hookers!

– Oh, so it is the whores?

– I have never been inside there! But … whores have this ugliness in them. They are the ugly people doing the things that are authentic. They don’t pretend. They have great feelings for bad music.

– This is what I saw in Liège in the 1970s when I was there and taught young musicians from there. At their examination, they did it in their own ways, well, … possibly it was to some extent my way.

– They played their own bad music.

– By the way: Do you play anything yourself?

– A little, but just for myself. Never in front of anyone.

– You should invite some of these Liège musicians. They play everywhere in Europe today. You don’t need to feel ashamed with them. Or, … you should let them invite you.

– I believe I write better about music, than I’m playing it. And I thing this choice is better for the world.

At this point Mengelberg creates a little wordplay, answering my last phrase with,

– Beckett for the world! Beckett, the writer …

– Samuel … one of my big heroes.

– Mine too. In his writings I find something very close to .. ..æærch-ææ-ææ- chchchchch, (Misha is demonstrating ugly music).

– And this returns us to where you started, with the Dadaistic dimension.

– Exactly.

– … which reminds me of how wrong Milan Kundera was in the title «The Unbearable Lightness of Being». The meaningful, Beckett-inspired formulation should be the direct opposite, «The Bearable Meaninglessness of Being».

– Yes, that is the only correct conclusion!

– I see a clear relation between your form of music, and this form of literature, Samuel Beckett, James Joyce, where the meaninglessness is made into the whole point. The meaning lies in the meaninglessness.

– Yes, (laughter). All these strange authors. Yes, it is possible to see such a connection.

– Have your original dream of becoming an architect – or architecture in general – and starting to study architecture, any influence on your musical development?

– Architecture was in a way a family tradition. My grandfather was an architect. As many more in the family. But I never saw my grandfather.

– He was mentally ill. He came from a strict catholic background, a background he later broke with. He never went to church after that. He hated the church and everything it represented.

– At that time, around 1900, this was seen as madness. Those maintaining these views, had to suffer from dementia.

– He crossed that line. But he lived until the beginning of the 1940s. I remember my father saying to me on the way out, that he was on his way to the funeral of my grandfather. It is a pity, but I never saw him. [My father] also said that, yes, you would have understood him.

– On my mother’s side, I also had a grandfather who was an architect. He died in 1943, just after my father’s father. He wrote for a journal in Berlin, I never saw him as well. He was some kind of surrealist. But this I had to discover through what he wrote, a long time afterwards.

– Later, when I had chosen my rôle as a surrealist composer, I wrote theater music, too. This was the first time I met Dada, and I believe, the first time I used it. I wrote music for Wim Schippers, among others.

We should add here: Wim Schippers is a Dutch comedian with obvious Fluxus inspirations. Among his greatest works was the performance of the piece «Going to the Dogs». Six German shepherds was on stage for more than an hour. They played out a directed drama, where they read newspapers, quarreled about family affairs and watched TV.

The stage play started with the dog playing Hector urinating on the carpet on the stage. The play was performed only three times, during two days. Parts of the play can be seen on YouTube.

– I think we’ll stop here. I have enough material here to make many stories, whether they be ugly or beautiful, surrealistic or sousrealistic.

– I must say, for me, this has not been a weird conversation. Quite the opposite. I appreciated this. It gave sense, and meaning!

And I still have no idea of what I was part of,

this morning on a sofa in Molde.

Kwik kwek kwak!

However, what about the concert in Molde? Misha Mengelberg, 76 years old, from Amsterdam, with the 31 years old Tyshawn Sorey from New York.

A watershed performance in the Molde Forum — the Molde audience have not experienced anything like it before. The proceedings started with the information from the stage that Misha Mengelberg was stuck in the elevator. Something like this had never happened in the Forum before. Was it true? Or was it an intended gag? Had the concert started already? A warning of what was to come?

At last, Misha enters the stage. Walks very, very slowly in a circle around the grand piano, frail legged, with a cane as support. On his way to what? «Woff!», he says (barking? sighing?), evidently totally immersed in his own world.

He pulls himself together. Turns around and returns to the piano. Absentminded he lays the cane over the strings. While Tyshawn is wandering about with a terry-cloth as sound source, «woff!». We are starting to suspect something unconventional is afoot.

Then comes what an audience with conventional expectations would regard as the beginning of a (conventional) free improvised concert. Tyshawn playing hushed at the drum set. Misha by the piano, with his back towards us. This was actually – and unconventionally – the second part of the concert.

From there and onwards – until the sun had moved about 15 degrees further west on the sky – the lives of those present were altered forever, whether their expectations were conventional or not. Whether they understood it or not.

From the 15 minutes mark and onwards to the end, Misha does not play a single tone. Tyshawn uses whatever is at hand. A water bottle, the sound of his hair. While Misha makes not a sound.

Not a single one. However, never has an instant composer been so totally present. With tiny movements. Nevertheless so loudly speaking. A face turning very slowly halfway towards the audience.

A hand lifted in a studied manner and left hovering over the keyboard, before Misha – just as slowly – pulls it back, and the hand falls down into Misha’s lap.

Together, Tyshawn and Misha give us over an hour-long learning demonstration of a total deconstruction of our socially constructed expectations and prejudices of what a concert should be.

An experience, a performance that would have been worthy of a burlesque, Dadaistic Jacques Derrida. If we can imagine a burlesque Derrida at all!

It is obvious that a «concert» like this is completely impossible to review, whether objectively or subjectively. A traditional and modernistically inclined reviewer, demanding objective criteria, would fall flat on his face. Even a more open, post-modernistic reviewer looking for intersubjective meaning in the dialogue between performers and audience, would fall short of the task.

On the other hand, if we look at the event from a post-structuralist perspective, it is possible to see that the experience of the event concerns everything that happened within the cube making up the concert hall of the Molde Forum.

The bottles of water put out for the two performers on the stage. We must include everything that happened in the heads of all the approx. 2 + 400 performers within this cube. Even those that left the hall during the concert – as they told me afterwards because they «didn’t grasp a thing about what was going on» – played an active, participatory and art-generating role.

When this interactive work of art entered its last phase, Sorey disassembled the drum set, in a deliberately slow manner, in an eternal search for new sounds, new music, new art. With this, the work of art was completed. Our joint experience was perfected by this reference, from the parts back to the totality.

In this, the physical deconstruction of the drum set itself became a reflection of the deconstruction of our expectations. Thus, this «drummy» deconstruction was in itself a fabulous metaphor of the whole concert. And with this, the reductionist division between the whole and its building blocks was repealed forever. Beautiful? Ugly? Who cares? Attractive «music» from a fantastic concert!

Stop! Concert? No, not concert. Performance? No, more! Much more! Total art! Arty totality. Art and the social becoming one indivisible whole. Five stars? Six? Far from enough! I would need at least a dodecahedron to have stars enough for this.

Can’t those damned frogs just shut up!

Vondsten in het binnenwerk

Who else, other than Mengelberg, could issue a recording of his red-tailed African grey parrot on a record under his own name? The parrot rendered a Charlie Parker lick, before ending the recording with a scream.

As Misha says, the definition of music that brings you the furthest is that «music is what people choose to call music». On the other hand, a «bird song is [just] a bird song».

«Dada never created any interesting music. And [thus] I mean that Dada is one of the most important things that happened in art during the twentieth century.»

Life is too important not to guffaw about it!

These are the real findings on the inside of it all.

Text: Johan Hauknes

Photo: Jan Granlie

All section titles are names of tunes by Misha Mengelberg.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.